New data reveals how funding cuts and patchy records have reshaped youth club provision in Islington and across London.

More than half of youth clubs in England closed between 2011 and 2023, with around 30% of youth clubs in London shutting between 2010 and 2019 as a result of cuts to local authority funding.

Nationally, local authority spending on youth services decreased from £947 million in 2011 to £341 million by 2021, representing a nearly two-thirds reduction over 10 years.

Even in the capital city, eight councils do not directly run any youth clubs in their borough, they are: Kensington and Chelsea, City of London, Westminster, Brent, Hammersmith and Fulham, Hounslow, Waltham Forest and Sutton.

FOI responses from Hackney, Islington and Newham show that councils are often shifting from directly running youth centres to commissioning organisations to deliver services on their behalf.

Peel Centre childcare co-ordinator Jeana Kidd said: “When the youth clubs have been closing, there is nothing put in place to fill the gap, so kids are forced to hang out on the street.”

FOI responses reveal that this national picture masks significant differences between London boroughs, with some maintaining their provision while others experience substantial contraction.

Islington Council directly runs one youth centre, funds eight and supports 10 organisations delivering youth services, illustrating a reliance on commissioned partners.

Since 2020, one major site, Platform Islington in Holloway, has closed as a council-run venue. The council also commissioned new sessions across the road to replace some of the offer.

Just over 5600 young people attended Islington youth services in 2025/26, with more than half attending regularly, suggesting demand remains strong despite limited provision.

In comparison, Hackney now runs or commissions five youth hubs alongside around 20 partner-led venues, having recorded no council-run youth centre closures between 2020 and 2025.

This difference is likely down to budget usage, with Hackney consistently allocating more to its youth services than any other borough.

The biggest loss was seen in Newham, which has lost 13 of its 18 youth centres, making it one of the most severely affected boroughs in the city.

Newham Council were also unable to provide detailed data when approached for comment, suggesting a lack of consistent monitoring of youth services.

National Officer for the Community, Youth and Not for Profit Sector, Andy Murray, said: “The reality of such underinvestment and the scale of failure by previous governments to young people…shows the very real impact of austerity on the life chances of young people.”

The National Youth Agency suggested the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the decline, with one in five youth clubs nationally struggling to reopen after lockdowns.

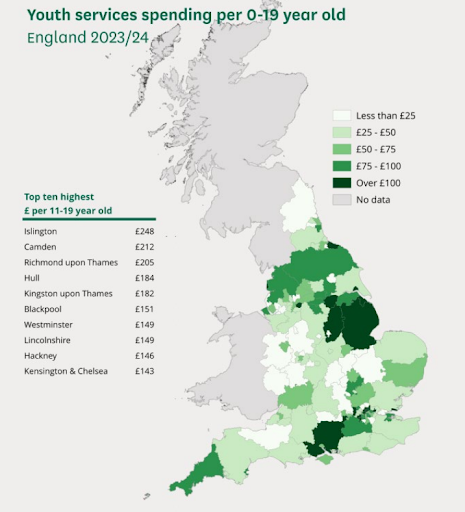

This is backed up by Islington’s youth service spending per 0-19-year-old dropping from £1625 in 2019/20 to £248 in 2023/24.

Kidd said: “COVID frightened a lot of adults, and that fear was transferred onto their children, so now anxiety has built up, and they don’t want to come out.”

Young people affected by youth club closures are also more likely to underperform at GCSE level and 14% more likely to offend, underscoring the long-term social cost of reduced outreach for young people.

Kidd explained: “Latchkey kids benefit more because their parents may be too busy, so if they’re looking for work, we’ll help you write your CVs, or if you’re struggling in school, we’ll find out why, we’ll help you revise.”

OnSide research found 93% of young people who attended a youth centre reported a positive impact, reinforcing claims from youth workers that early intervention remains critical.

Survey respondents from across London echoed concerns about the loss of youth spaces.

One young person said: “Now I’m older, I have fond memories of my youth club back home. It was the epicentre of my childhood social life.”

Another said: “We lost a safe space to socialise, take some ‘you time’ away from home, and importantly, a space that allows kids to be kids safely in a city that can be cruel.”

Despite local councils funding outreach work and partnering with youth clubs, Kidd said youth workers are still left trying to fill widening gaps.

She explained: “We do detached work, go into schools, talk to Year 6s and 7s, run open days, and use social media, but it’s harder when there are fewer spaces.”

Taken together, council data, national research, and lived experiences suggest youth provision in London has become fragmented, harder to measure and increasingly dependent on postcode.

Where a teenager in Hackney may find somewhere nearby to spend their time, a teenager in another borough may find the doors closed with very little explanation and nowhere to spend their time but out on the streets.

Feature image credit: Lift Islington

Join the discussion